World War II brought with it the very real possibility that Britain may not be able to feed its population as it was reliant on overseas imports (Spencer, 2002). To futureproof against national food shortages, the government introduced rationing across Britain from January 1940. Rationing did not end (in entirety) until 1954, some 9 years after the war had ended.

Overseen by the Ministry of Food, every man, woman and child was given a ration book with coupons which were essential in being able to obtain food, and they had to be registered with a particular grocer or butcher. The image to the left is of a child's ration book (you can see this in the bottom right corner text). Colour coding was an important identifier too. Pregnant women, nursing mothers and children under five received green ration books. Children between five and sixteen years old were issued with blue ration books and everyone else - i.e. most adults - were issued with a brown ration book.

A sense of fairness and everybody being 'in it together' underpinned the idea of rationing. Basic foodstuffs were rationed in a way that gave everyone a daily allowance of items such as meat and sugar. A points system was used for items such as tinned goods or dried fruit. In reality, there were differences in diet across the country. Those in rural areas had more space than their urban counterparts, enabling some to keep chickens and to grow their own vegetables.

'Fighting fit'

As Laura Dawes (2016) notes, keeping Britain fighting fit was considered by Winston Churchill himself to be an essential component in the war effort. There had been significant advances in the science of nutrition led by scientists such as John Boyd Orr, who had examined how poverty and poor diet impacted on health in the 1930s. He had calculated that only a third of Britain's population were receiving an adequate diet, but argued that the 'health line of the Home Front' would be as important as the 'Maginot Line' (Spencer, 2002: 314). Deciding what individual rations should consist of was clearly a vital task.

Three scientists at the University of Cambridge: Elsie Widdowson, Robert McCance, and Frank Engledow tested a diet of British produce that they hoped could be rolled out on a national scale and keep the populous healthy. Eight adults followed the restricted, experimental diet the researchers devised and were assessed as to their experience of disease, tiredness and body weight changes as well as their psychological wellbeing. Energy giving foods such as potatoes and bread were prioritized. The volunteer group were even given strenuous physical tests - hiking, cycling and climbing - whilst on the diet, and they stood up to the tests well. It should be noted, however, that children were not part of this study.

Rationing did account for children's particular requirements, notably the very youngest children. On one level children received less food than adults, such as half the meat ration, but alongside pregnant women, they were given priority allowances of milk. Early on in the war the Ministry of Health became concerned about vitamin C deficiency in babies and young children. Breastmilk only provides this essential vitamin if the nursing woman has a diet consisting of a good supply of fruit and vegetables. And as the medical research team had noted, a mother's diet was often the least adequate of all family members - notably in poorer families. Before the war, when there had been similar concerns, babies were given additional orange juice to supplement breastmilk to offset any deficiencies of vitamin C. Flu and colds were sweeping across Britain and a poorly child meant parents staying at home to look after them or indeed catching the disease themselves. Either way it meant these parents would be kept from their vital wartime work on farms and in factories (Dawes, 2016).

Getting children to eat vegetables could be a challenge and citrus fruit was in poor supply owing to shipping restrictions. One strategy tried by the Ministry of Food was to buy up an entire year's supply of blackcurrants to make puree and juice for babies and children (Dawes, 2016). H. W. Carter and Company, based in Bristol, created the product Ribena, which is still in production today. But there were not enough blackcurrants to make the syrup to supplement the children's diets. Research at Kew Gardens showed that rosehips were a powerhouse of vitamin C and when cooked and strained made good jam, syrup and cordial. Children in country areas were encouraged to collect rosehips as part of schooling or as Girl Guides or Boy Scouts. Rosehips were sent by rail to an assortment of companies called the Rose Hip Products Association and were made into National Rose Hip Syrup to a standard approved by the Ministry of Health. To get its full nutritional import it needed to be drunk within 6 months as its vitamin content diminished over time. So potent was the syrup that one teaspoon a day supplied half a child's vitamin C requirement (Dawes, 2016).

Dietary advice

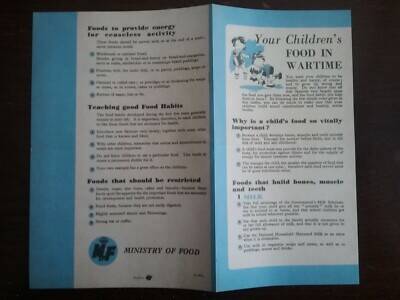

The Ministry of Food produced pamphlets to encourage families to ensure their child maintained a healthy diet. 'Your Children's Food in Wartime' was produced in 1944. It outlines why children need a healthy diet. Milk, milk, and more milk seem to be the watchwords of the leaflet's first page, in order to build bones, muscle and teeth. Then energy giving foods such as wholemeal bread, potatoes, oats and sugar/fat are emphasized. The Ministry of Food advised on meat, fish, eggs, cheese as well as salad and other vegetables and fruit juice. The pamphlet took pains to stress that children were to get their full ration of milk and other foods and these were not to be used to supplement other - perhaps adult -members of the household.

There is advice in the pamphlet on how to introduce new foods and it takes pains to encourage mothers to make food attractive. This must have tested the prowess of many a cook given they were working with restrictions. We wonder how many people were successful in encouraging their children to eat 'thinly sliced raw young turnip or swede'! Recipes were shared to ensure families had a good nutritional intake and children were given treats at celebratory occasions. Marguerite Patten (1995) republished some of these recipes and whilst they are remarkable in their creativity it's hard to imagine cooked and mashed parsnips, mixed with sugar and banana essence - masquerading as a banana sandwich - as a delicious treat. Jelly and blancmange from a rather synthetic flavoured powder mixed with fresh milk, or powdered, evaporated or condensed household milk, were treats many children could enjoy during wartime. Dishes such as a basic sponge pudding with jam or syrup were even given names such as 'patriotic pudding' in a 1939 Board of Education booklet to bolster the idea that what you ate was inextricably part of the war effort.

Getting the message across

Cheery adverts were employed to further encourage families to feed their children a healthy diet during a time of shortages and rationing. 'Doctor Carrot' is a good example of this. Carrying a doctor's bag with 'vitA' labelled on its side, the humble carrot is the 'children's best friend'. Carrots were in plentiful supply and radio slots and cinema 'food flashes' encouraged making dishes such as carrot pie, carrot fudge and carrot pudding (Dawes, 2016). Whether such campaigns did much to encourage children to eat the said carrot is another thing and the incessant chirpiness of the approach may well have grated on a populous longing for a less restricted choice of foods. The Ministry of Food also encouraged families to use food wisely and avoid waste. Waging war on waste, such as food waste, was a vital part of doing one's bit for the war effort.

The role of schools

Schools played an important role in ensuring children were fed as they do today. Schools were not immune from food shortages and children received what was cheap and available at the time. There was often a reliance on canned foods, resulting in the ubiquitous spam fritter or rissole alongside some potatoes and peas, followed by rice pudding. School meals were generally cooked on the premises enabling cooks to be flexible as to what foods were available. By 1944, there was a legal requirement that schools meals were balanced and nutritious and free for those in need.

Some schools in World War II - notably in urban areas - expanded their role beyond feeding children to feeding adults too. Communal feeding centres were opened during wartime and catered for a wide clientele and some were housed in schools. In London especially, people whose homes had been bombed were glad of an emergency place to eat until they got settled. Churchill, however, disliked the term 'communal feeding', seeing it as related to the workhouse and communism. The rebranding of these centres as 'British Restaurants' gave them patriotic appeal (Atkins, 2011). As the food was off rations, nutritious and cheap, for many in London especially, British Restaurants were very welcome and a first experience of eating out. This said, looking at the nation as a whole, most people still preferred eating at home (Zweiniger-Bargielowska, 2011).

Was rationing and the wartime diet a success?

It has certainly been argued that the health of the nation was not diminished by rationing and the wartime-diet: indeed if taking figures overall, child mortality rates were lower and children were 'taller and sturdier'. Tooth decay, deaths from tuberculosis were down and anaemia in children and women had decreased despite shortages of medical staff: many of whom were engaged with the armed services (Spencer, 2002: 317-8). The diet that was encouraged certainly had some treats for children but was essentially a diet that was rich in protein (albeit not a huge amount from meat), had due regard for children's energy needs, and was mindful of the need for vitamins and minerals. Wartime was also a period that recognised that nursing mothers need a good diet too to nourish themselves and their infants.

However, there is an alternative perspective to this rather rosy view. There was little detailed nutritional monitoring, making a detailed analysis of children's nutritional status impossible to assess; the needs of adolescents were not considered fully during rationing; vitamin supplements (for pregnant and nursing mothers and young children) had a poor uptake amongst working class families; and although infant mortality did fall overall - when you drill into the figures more closely - wartime rationing made little difference to the mortality rate of infants from the poorest quintile group. Furthermore, whilst food rations were badged as fair and equal for all, little account was taken for differential needs (beyond nursing and pregnant mothers and very young children) and the distribution of food within households remained unequal. Many working class mothers went without their meat ration to ensure their children and especially their husbands received a larger portion (especially if in a manual job).

Social class impacted on one's access to food. Restaurant meals were never rationed, wealthier people could augment their diet with foods that were off-ration, and it was generally felt that the wealthy got preferential treatment in shops (Zweiniger-Bargielowska, 2011). In short, for all the championing of wartime rationing as offering fair shares for all, the reality was that social class continued to be a factor in what children and their families ate and in their health outcomes.

For sure people did get fed in hugely challenging times, but few would want to go back to the restrictions on food that were experienced in wartime Britain (and for some time afterwards). Choice over what one eats rather than government control is something many would not want to give up. However, the idea that there everyone should be able to access a healthy diet is one that should surely form part of any national food strategy. The experience of wartime rationing shows us that a far more nuanced approach to thinking about access to a healthy diet is vital, in particular - one that looks more closely at the impact of social class.

References

Atkins, Peter J., 'Communal Feeding in Wartime: British Restaurants, 1940-1947', in Food and War in Twentieth-Century Europe (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011, pp. 139-153)

Dawes, Laura (2016) Fighting Fit: The Wartime Battle for Britain's Health, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Patten, Marguerite (1995) The Victory Cookbook, London: Hamlyn.

Spencer, Colin (2002) British Food: An Extraordinary Thousand Years of History, London: Grub Street.

Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina (2011) ‘Fair Shares? The Limits of Food Policy in Britain during the Second World War, in Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Rachel Duffett ad Alain Drouard (eds) Food and War in Twentieth Century Europe (Farnham: Ashgate), pp.125-138,

Image references

Artist unknown (1939-45) 'Doctor Carrot' poster, courtesy of https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doctor_Carrot_-_the_Children%27s_Best_Friend_Art.IWMPST8105.jpg

George Chernilevsky, 'Blackcurrants in a Basket', courtesy of https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blackcurrant_in_basket_2021_G1.jpg

Ministry of Food (1944) Your Children's Food in Wartime, MoF.

Sample child's ration book from World War II, courtesy of https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sample_UK_Childs_Ration_Book_WW2.jpg

Add comment

Comments